Writing: Table of Contents

Four Original Poems

The Gulf Of Mexico

I owe my only life to the Gulf's dewy dispensations.

Scratching here, scratching there, my orbs of corn

And melons will swell only as she swells.

My God, what will!

I think, down at the bottom where the deepest drafts are drawn

Sulfuric craters still steam and gurgle,

Pearly crustaceans must swirl and mingle.

A pearlescent place.

Drawn up and over, vaporized, the waters go wanting,

Looking for Laurentia. Her earlier lover.

Somenights when the winds are simmering

Thinks I, the two of them:

"Oh, Laurentides...

In an earlier age my powers were totally

Undiminished.

I brought you to me directly,

Subterranean.

Queenly Superior, take testament of this mystery

In the chased channels of your eastern bathymetry.

Oh...

Until the end of time?"

The Goose Hunt

Dragging our accouterments through the winter checkerboard

white snow, black marsh, white snow

my brasses glint and clank, my white furs gleam with new oil,

and my little servant, Joseph, and I, having taken four birds,

gift the biggest to the judicious and chatterbox sleddogs.

After lunch, they lick themselves tidy and with breath steaming

we proceed over the iced sloughs, high-pawing over the snowbanks

and streaming over the trails. But when the noon sun slushes us out,

My litle servant, Joseph, and I, distracted at the reins

by the silver and ceramic dainties of tea-time on the sledge,

go crashing in the river. The eight dogs yip and paddle,

but we cling to the lufted lapels of my white furs,

gleaming with new oil, and it all goes by.

Saw-Whet Banding Station

The bitter taste of coffee, rising -

The face of a full moon, resting -

The bed of a truck, sitting down.

Watching the ashen plumes of goldenrod,

the trace of maple canopies,

the broken plane of a beaver pond

recede down a winding road -

See no deer, hear no owl.

The wind passes over my ears.

Posted 18-Oct-2024

Xin Qiji

I have seen that mystery there, reclining,

ball in one hand, long dart in the other,

and heavy measure on the table.

She sits on dun wicker, by a long pane

of reradiated Autumn heat. She smiles

and tells the story of Grandfather,

his time in the underworld

and the noise there ------ A

dream of circumpolar sea

when it is warm,

when birds land,

and a chest is full of linen.

I have seen that mystery there, reclining,

when an old man wakes and says:

"What a cool and lovely Autumn."

Posted 13-May-2024

The Venture of Islam, vol. 1

The intent of this post is to briefly outline an apparent problem in Marshal G.S. Hodgson's account of the Ummayad-Abbasid transition. This account can be found in the chapter "The Islamic Opposition, 692-750", pages 241 to 279. Contemporary scholarship seems to refer to this period as the "Abbasid revolution".

Hodgson introduces in this section the notion of a category of people he terms "The Piety-Minded". Comprising this group:

- The Mulawi: non-Arab local elite subjects of the caliphate, who begin to convert to Islam. Their conversion does not suffice to give them entrance to the political, social, and economic advantages that their Arab counterparts enjoy, and who thus seek greater legal equality via their common religion.

- Islamic judges, Quranic scholars, and Hadith-reporters. Variously discontent with the percieved lack of religiosiy among Ummayad political life and seeking to legitimize their factions as legal and religious experts.

- Khariji, revolutionary-military zealots, who precipiate internal rebellion on accusations of lack of religiosity among Ummayad military and political elites.

- Ali'd partisans, a category overlapping the previous three, who go on to develop the incipient Shiaism of this time.

Although it is clear that these groups are in communication with one another and are alike in their opposition to the ruling regime, the supposition that ought to be able to act as a coherent political force needs to be substantiated. I feel that Hodgson fails to elaborate this sufficiently, and that he leaves open the question of what really drives the rise of the Abbasd caliphate, and what prevented the oppositional groups to cohere as such, and to what extent the oppositional "Piety-minded" actually coheres as a historiographic category. Moreover, I worry that given Hodgson's personal religious impulses (he identifies himself a Quaker) and his orientation towards analyzing this historical period as a development of religious consciousness, something may be left out of his account. Hodgson's repulsion at the militarism of the age stands out: for him, the use of violence in consolidating imperial power marks a failure of the Piety-minded to further their goals, and a stagnation in the course of development of religious consciousness. Of course the Prophet, his companions, and the later Khariji and many of the Ali'd partisans have no total repulsion to the use of warfare themselves.

The role that regional rivalry and differential development play in the contest over the central imperial authority at this time seems to be underelaborated. Previous sections discussed, insufficiently, the problems of extracting tax revenue from areas of very diverse forms of economic organization, and the partiality of particular regional or tribal groups to themselves against their competitors. The level of state investment, long-distance trade, and mediation by local officials, all seem to vary significantly from region to region. Also complicating analysis is the differential effect of warfare, which enriches some (via wartime plunder) and impoverishes other groups (by might collapse trade or hamper state investment). Any rising power had to make use their particular advantages, without alienating the opposing groups so profoundly as to make their assumed position untenable. It does not seem like any particular faction among the Khariji, the Ali'ids or the more timorous scholars ever could provide enough leverage to justify the championing of their cause. Hence the Abbasids come to power on the back of a revitalized military organization sufficiently competent at quashing regional rivalries.

This course of study seems to intersect productively with my ongoing reading of Jarius Banaji, but I am not yet confident in my grasp of the history and the theoretical apparatus to write anything further.

Posted 9-Dec-2025

Frederick Jameson's "An American Utopia - Review and Response

This review was removed 30-Sep-2025 and is currently undergoing re-review

Posted 21-Dec-2023

Review of Richard Lewontin's "Trhe Triple Helix"

Richard Lewontin's "The Triple Helix" is principally concerned with breaking down two dogmatic principles in biological thinking: that environments determine genotypes, and that genotypes determine phenotypes. Even in introductory textbooks, it is never expressed as unequivocally as this, and in our day-to-day lives we hardly live as if these relationships are so simple. Nonetheless, this simplified model of relations between environment, genetics, and organism, become fixed in our thinking over time, simplified after repeated uncritical usage in the classroom. Frequently they are explained through simple case studies; discussed at length in my high school classroom was the English black peppered moth, Biston betularia, which experienced a rapid and noticeable change in genotypic and phenotypic composition in response to a rapidly changing environment. When discussing genotypes, some of our lessons modeled the experiments conducted on Drosophilia flies, a very common medium of experimentation for developmental and genetic biologists.

These examples are not false, and neither are the basic principles they explain. However, if we want to be good biologists, we must come to fully understand the complex interpenetration of organisms, their genetics, and their environment.

The genes of an organism are a fundamental input in the outcomes of its development, Lewontin admits. The connection between a particular gene and a particular phenotypic outcome, however, is extremely convoluted. Most distinguishing phenotypes are directly influenced by a large number of genes, and indirectly by an even greater number. More importantly, an organism's environment significantly affects the way genes are expressed. Genetically identical organisms can have significant developmental variation when placed in different environments, or even when placed in the same environment! And some genetic variation, while producing developmental variation in some environmental conditions, does not produce developmental variation in other kinds of environments!

These facts are made even more complex when we consider mechanisms of natural selection. For example, a species may possess a mutation of a particular gene that generally produces a desirable physiological change, improving the fitness of the species. Over enough time, we would expect this variant in the organism to become dominant, resulting in evolution of the species. There may be a second mutation, of a different gene, that also produces a desirable change, also improving the fitness of the species, etc. It is not uncommon, interestingly, for these two desirable mutations to interact negatively, meaning the presence of one or the other is beneficial, while the combination of both is undesirable! This is precisely the situation in Moraba scurra, a grasshopper Lewontin examines to illustrate this point.

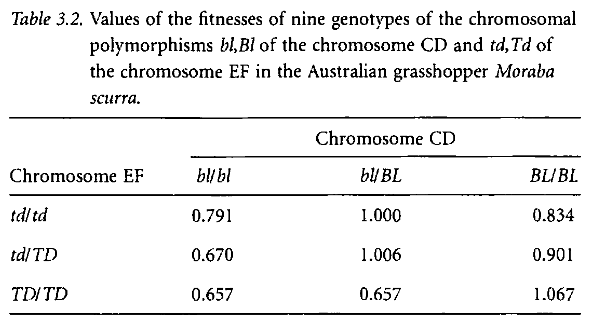

The first table illustrates the fitness values (how evolutionary fit) of given combinations of particular genotypes in this grasshopper. A higher value is a higher chance of surviving and passing on those particular combinations, and vice versa. One genotype is not universally preferable; its fitness always depends, in some complex relationship, on the other gene as well.

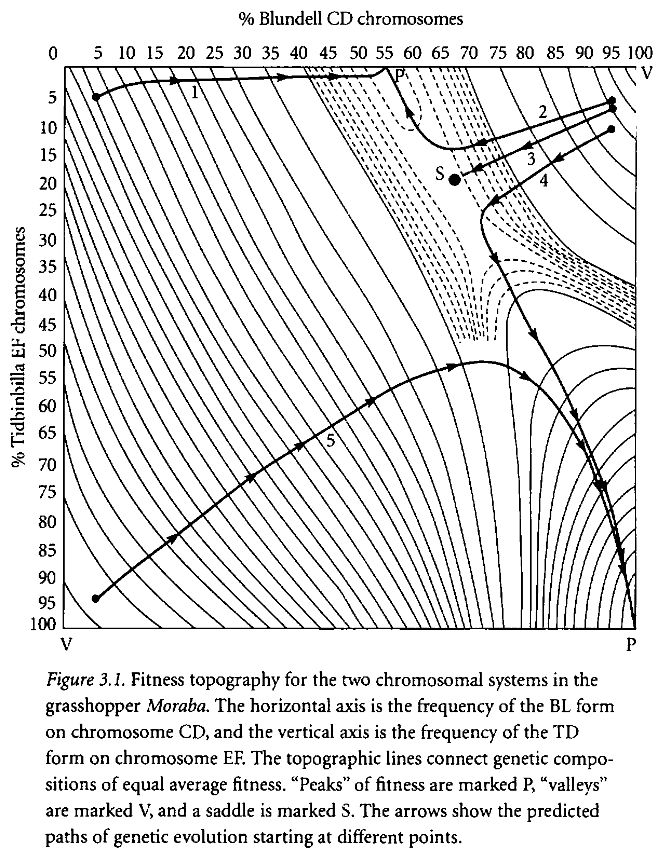

The second table illustrates the same point, with genes represented as percentages of the population rather than as specific combinations. The arrowed lines show the movement of the population average given various starting points; ie, change in genotype distribution over time. If, for example, if a population of grasshoppers began with a genetic makeup mostly possessing the TD/TD and bl/bl genotypes, (the bottom left corner), natural selection will produce first a population mostly consisting of td/TD and bl/BL genotypes, and only then for the more desirable TD/TD and BL/BL genotypes! It is not possible to move linearly from bl/bl to BL/BL, because the intermediate combination has a very low level of fitness. Similarly, given other starting points of genetic variation, it may be impossible to move to the most fit genetic type; this is the situation illustrated by the lines of motion in the top half of the diagram.

One can imagine how much more complicated this situation gets when there are even more kinds of genetic variations at play.

The more tricky relationship is the one between an organism and its environment. Lewontin begins this section by critiquing the concept of an ecological niche. Although a fundamental piece of our vocabulary in the ecological sciences, it does not hold up well to scrutiny. Behind the concept of an ecological niche is a static, unchanging environment, perforated in various places to allow organisms to "fit in". The roles available to play in a given system have already been determined by the environment. What is missing from this picture is the way organisms construct their own environments, and the way every organism is an element in the "environment" of every other organism! The perspective we ordinarily use reduces the organism to simple ecological function, rather than seeing them as unique actors.

In order to more completely understand organisms, then, we must see environments as the "penumbra of external conditions that are relevant to an organism because it has effective interactions with those aspects of the outer world" (pg. 48). Penumbra is an astronomical term that refers to the half-dark, half-lit region at the edge of a shadow cast by an object. What this view entails is that every environment is a zone of ambiguity, which is constructed partially by its organism and partially by the rest of material reality.

This is very easy to see in animals such as beavers, which literally construct their environments by building dams, raising the water table, constructing shelters, and changing the composition of woody plants in the nearby environments, as well as the composition of aquatic and semiaquatic species living in the modulated environments. Other situations may not be so simple.

Here is another example drawn from my own experiences: let us take the oak savanna ecosystems, which are frequently subject to human-induced wildfires. Mature oaks have thick bark which protects them from these wildfires, while many other trees are unable to withstand them. Dead oak leaves are thick, full of tannins (making them difficult to decompose), and persist on the tree for a greater time period. They also curl and are rigid; these all combine to create a humus which is airy, dry, and fuel-rich, which increases the frequency and intensity of fires!

It may be easy enough to say that the encouragement oaks offer to fires is not a result of their "activity", but is simply determined by their genetics. This is not untrue. But, if we are interested in forming a more sophisticated research program, we might study, for example, what kind of changes in oak development are induced by it being exposed to a wildfire, or other environmental conditions. We might see that the changes the oak undergoes in response to its environment go on to affect the environment itself. We would have a dynamic system of parts always affecting one another, and then recieving their own effects through their surroundings; the causal relationships are circular, not linear.

Lewontin's book is full of more complex arguments and illustrative examples. I have attempted here to reproduce some of the more interesting and fundamental points, but I have hardly expressed the full scope or depth of the work. I would recommend it very strongly to any person studying, or even interested in any kind of biological science. Due to its age, and the frequent changes in these fields, I would not be surprised if some of the particular research discussed is slightly out-of-date; nonetheless, the fundamental problems discussed are still prevalent in so many of my classes today. I hope to make the kind of complex thinking he demonstrates useful in my own studies.

Posted 8-Apr-2023